This article originally appeared on my game development blog, and has been reproduced here for students to see. It has been lightly edited. This is an example of how I approach encoding rules once playtesters have played the game. It’s the difference between telling someone in front of me, and writing for someone I’ll never meet.

Die Rich is a card game I developed… I want to say early 2020, late 2019. The idea comes from a long time ago, and it’s built around a design I used for referencing a thing in a RP space, of the Carthaginian General Hannibal.

The thing is, something happeend in 2020 (like, all of 2020), and that meant I never developed the rulebook for it. I’d played the game, before I ever made any of the cards, and I’d tested it, I knew the game worked… but I never wrote down the rules.

Now I don’t know if I remember them, exactly.

But I do have a deck of the cards, so I can play the game, and see the problems, and reconstruct what I generally know. Then I’m going to construct what I need the rules to cover, and you can read that. This is how these rulebooks kinda got made.

First, you set the game up. This game uses slugs: Stacks of cards that have a trait. I need the Scoring cards to show up roughly equally spaced between one another, so we make a set of slugs to make the deck. Now, there’s a mathematical way to do this, where subtract starting hands, divide the remaining cards into four stacks, shuffle the scoring cards into each of them, then stack them up, with the Hannibal at the bottom. That’s the math of it, but phrasing it needs to be done in an approachable way:

- Remove the four scoring cards from the deck, and shuffle the remaining cards.

- Deal each player a face-down hand of four cards.

- Then deal the remaining cards into four piles.

- Shuffle the four scoring cards

- Put one of each scoring cards face-down on top of the piles.

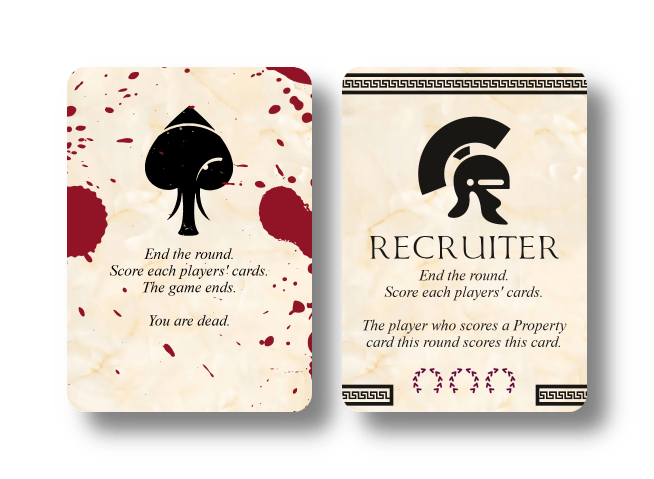

- Shuffle the pile with the blood-stained Final scoring card

- Then shuffle each of the other stacks, and put them on top of the pile with the Final Scoring card in it.

- The deck is now ready to go!

Okay, that gives our direction for the setup. That’s good, I like that.

Next up, we need to describe the play pattern of each turn. Each player is going to pick a card from their hand to play into a tableau in front of them, and when the scoring cards come up, those cards are then ‘scored.’ That’s what the laurels are for on each card – that’s how many points that card is worth.

Every time a scoring card comes up, you score all your cards. Each type of card in your tableau is ‘won’ in different ways. It’s possible for a category to have nothing but losers, mind you!

- Property cards are rewarded to the player with the single largest property.

- Politics cards are rewarded to the player with the most supporters

- Market cards are rewarded to the player who has the cheapest markets

- Bacchanal cards are rewarded to the player who has one.

How then do these cards differentiate themselves in play? Property, Politics and Markets all have a I-VI bar on them. For each type of card, this bar means something different.

- Property cards: the number indicates where the property is. You want to get property in different, adjacent areas, to make more control over areas. This means you want contiguous numbers, if you can. The cards at either extreme – I and VI – have the highest value, because there are fewer cards for them to connect to.

- Market cards: the number indicates the prices your market charges. Lower numbers are safer, more sustainable. Market cards can score multiples at once – but it’s much easier to have markets broken by another player’s choices. So if you have say, two five-value market cards stacked together, you may be looking at a lot of points, but then any player who can play any market that’s cheaper is going to not just get their points, but destroy your points.

- Politics cards: the number indicates your position on a left-right spectrum. You earn all the political support that’s nearest to your position, with draws being dropped. So if you take 3, and another player takes 5, you get 1, 2, and 3, and they get 5 and 6.

- Bacchanal cards: Only one person can have a Bacchanal card. When a player plays a Bacchanal card, all the other ones in play get discarded. This means that if two players play a Bacchanal at the same time, they cancel each other out.

The cards have text on them to remind you of some of this – but there are details, like the Politics cards don’t explicate what ‘most supporters‘ mean. That means that needs a clear example, probably with a diagram.

Markets can have ties, and Bacchanals can’t, though. If you and I both put down a market value III and you do too… that’s fine. We can coexist. We’ll even score them, at the end of the round, unless some other player undercuts both of us.

As for politics? It’s possible for nobody to win. If one player takes the I and the other takes the VI, those two players have equal area control (I gets II and III, VI gets IV and V), and then when the time comes to grade politics? Neither of them succeeds.

Okay, that’s the rules for scoring, but we haven’t cleared up how you add cards to your tableau. That means we need to talk about the actual steps of play. You set the cards up, you understand how to value them, and now.. What.

- Each turn, players pick up to one of the cards in their hand, and put it into their tableau face-down.

- When every player has chosen their card, or chosen not to place one, they flip it over.

- If a player play a Bacchanal discard all the other Bacchanals any tableaus.

- If two players play a Bacchanal on the same turn, both are discarded.

- If a player plays a Politics card and they already have a Politics card in their tableau, they pick one to keep and discard the other

- If a player has not played any card, they can discard any number of cards from their hand.

- Then, each player draws cards until they have four cards in hand.

Okay that’s our player loop. But we’ve looked at the drawing of cards, and that’s a problem, because that deck has those Scoring cards in it. Those scoring cards have on the back of them a symbol so when they show up, people get to know that scoring is about to happen. Then…

- If a Scoring card is revealed, players flip it over and set it next to the deck while they draw cards up to their four cards

Alright, hang on, in a four player game, there’s very much possible a chance that if all the players throw out their hands, you could see sixteen draws and that’ll get multiple scoring cards revealed, so we need to make a note for that.

- If one or more Scoring cards are revealed, flip them over and set it next to the deck while players draw their cards.

Then there needs to be a rule about how to handle scoring.

- Once one or more scoring cards have been revealed, it’s the end of the round. Players can play one more turn, and at the end of that turn, players score their cards.

- All the market cards that have the shared lowest value are scored.

- The player who has the largest property scores one of those cards of their choice

- The player who has the most political support scores the politics card

- For each type of card in your tableau that you can score, turn it around so the wreaths are pointing up. They’re not part of your tableau any more.

- Check the scoring cards – they give special bonuses to players who perform best in one of the three categories of Property, Politics and Bacchanal this round.

And… that’s it?

I think?

The final scoring card, the Hannibal card ends the game. That doesn’t get anyone any bonus points.

Upon playtesting with some students, I got a new detail to work with: It’s possible riiight at the end of the deck that a player doesn’t have the means to restock their hand. This creates a slightly fiddly rule. I don’t want to make it so players have to monitor who drew what, because what cards go into your hand is technically hidden information, and I don’t want to make the draw into a slow, monitored specific.actions. So this creates a little bit of wiggly feelings – do we just deal with it when some players’ final actions are made with fewer cards? I’m not sure it’s a bad thing.

The problem it presents, though, is that it means that the order of drawing suddenly becomes something to track. Right now you don’t need to.

I think that as a result, when the deck runs out, you just shuffle the discard pile, stick it down and the players draw their remaining cards from it. This is as best I can see the simplest method?

Alright, so that’s… our basic outline? That’s all the rules required for the game. Now the next struggle is to get these into a rulebook.